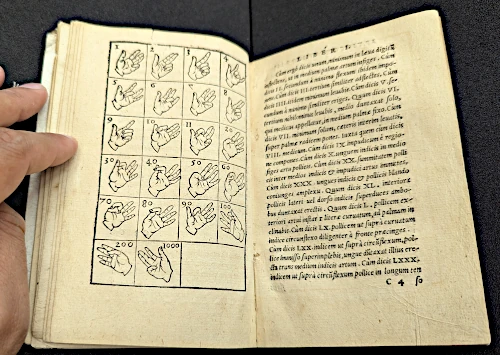

With the generous support of the Central European History Society, I traveled to Germany this summer (2025) to conduct pre-dissertation research. The trip was exceedingly fruitful. My dissertation project examines the significant roles of visualization and embodiment in premodern numeracy across various disciplines. Specifically, I am interested in a diagrammatic and gestural tradition central to medieval mathematics, culture, and daily life but often overlooked by scholars: the ancient tradition of finger reckoning. For centuries, people depicted, felt, and performed numbers using this powerful system, which allowed them to count up to one million using only their hands. The diagrammatic tradition of finger reckoning remains far from fully understood; most manuscripts have never been closely examined, and the relationships between them are often a complete mystery. These diagrams and texts raise important questions about medieval culture and cognition, as well as the production, visualization, and circulation of knowledge.

I spent three weeks in August conducting archival research in Munich and Berlin, where I consulted dozens of medieval manuscripts and early printed books. My original proposal included visits to other Central European archives whose holdings are comparatively limited for my project, but the extraordinary richness and density of the materials I encountered at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (BSB) and the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (SBB) made it both natural and advantageous to adjust my plans and focus on these two libraries. As often happens in archival work, the sources themselves reshaped the itinerary.

Over the course of the trip, I examined a wide range of materials, spanning from the early Middle Ages to the early modern era. Among them were some of the most crucial sources for my project, including two medieval manuscripts at the SBB and two others at the BSB that contain remarkable diagrams illustrating how to count on the fingers. One of the most significant outcomes of the trip was the discovery of finger reckoning materials embedded in unexpected epistemological contexts. Namely, in addition to finding information in computational treatises (as expected), I discovered diagrams and textual notes in theological works, genealogical materials, and texts related to astrology and magic. These findings broadened my understanding of how finger reckoning circulated across medieval and early modern knowledge systems. They confirm that finger numeration was not a narrow technical craft but a flexible and culturally pervasive mode of visualizing, feeling, and thinking about numbers.

This research trip has had a substantial impact on the development of my doctoral dissertation. I returned with hundreds of notes and photographs as well as an expanded corpus of case studies that will shape the argument of the dissertation. A particularly enriching moment was the opportunity to consult several editions of the short treatise Abacus by the sixteenth-century Bavarian humanist Johannes Aventinus (and, by coincidence, in the BSB’s “Aventinus” reading room). The Abacus is itself based on a manuscript that Aventinus discovered at the abbey of Saint Emmeram in Regensburg, written five hundred years before him. Five hundred years after him, I also had the privilege of consulting the manuscript that is, in all likelihood, the very one Aventinus had used. Encountering these documents placed me vividly within the long history of their transmission.

Although many of the documents I consulted during this research trip were digitized, I ultimately returned with renewed validation of my previous experience that direct engagement with the sources is irreplaceable. A hands-on approach often revealed details that digital images tend to obscure, such as signs of wear and tear, as well as aspects of scale and color.

I am deeply grateful to the CEHS and its members for their support, which made this research experience possible.