Supported by a CEHS travel and research grant, I conducted archival research in Germany in July 2025 for my dissertation, “Navigating ‘Bad’ Sound: Global Knowledge and Experiences of Noise across Germany and Japan around 1900,” which explores how different frameworks for understanding noise took shape across Germany and Japan amid globalization around 1900. During my research trip to Germany, I focused on gathering primary sources related to everyday standards of noise in Germany around 1900.

More specifically, I visited the Landesarchiv Berlin, the Staatsarchiv Hamburg, and the Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg, Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg for three weeks. The main purpose of this trip was to collect archival documents that shed light on how the German public reacted to daily noises arising from industrialization and urbanization and how they developed everyday frameworks for understanding these noises between 1870 and 1930. At these three archives, I identified and collected a wide range of documents produced by various government organizations in Germany, including the police, medical councils, city administrations, and railway administrations.

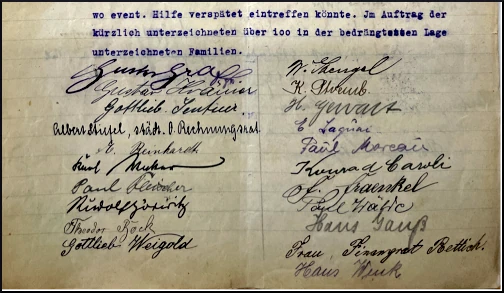

My archival work in Berlin, Hamburg, and Ludwigsburg resulted in three significant findings. First, I was able to identify the major sources of noise in Germany around 1900. Amid rapid industrialization and urbanization at that time, trains, factory machines, and automobiles emerged as the primary sources of noise. Second, analyzing these archival materials allowed me to see how the public developed strategies to cope with the noise around them. For example, residents submitted formal complaints with their names and addresses to local authorities (see image above). Various officials, including the police, city administrations, and medical councils, intervened in complaints and communicated with residents to solve problems caused by noise. Third, the documents reveal diverse motivations behind public opposition to noise. Namely, people sought to eliminate undesirable sounds around them because they were concerned about property devaluation, feared negative impacts on their health, or were simply unable to sleep or work.

Further analysis of these documents will constitute a major part of the final two chapters of my dissertation. Comparing quotidian experiences of noise across different regions in Germany as well as examining more closely the interactions between the public and local authorities will lead to a deeper understanding of how ordinary people shaped their way of knowing noise across the country around 1900. In addition, the documents will allow me to capture the similarities and differences between German and Japanese experiences of noise during this period. After I gather primary sources in Japan next year, I plan to compare how the German and Japanese publics reacted to daily noise, which will enable me to reinterpret noise at the turn of the twentieth century from a global perspective. I am deeply thankful to the CEHS for its generous support of this archival research.